Governing Through the Cloud: The Intermediary Role of Compute Providers in AI Regulation

Compute providers can play an essential role in a regulatory ecosystem via four key capacities: as securers, safeguarding AI systems and critical infrastructure; as record keepers, enhancing visibility for policymakers; as verifiers of customer activities, ensuring oversight; and as enforcers, ...

Below is the executive summary of our recently published paper "Governing Through the Cloud: The Intermediary Role of Compute Providers in AI Regulation." You can find the paper on the Oxford Martin School's website.

Abstract

As jurisdictions around the world take their first steps toward regulating the most powerful AI systems, such as the EU AI Act and the US Executive Order 14110, there is a growing need for effective enforcement mechanisms that can verify compliance and respond to violations. We argue that compute providers should have legal obligations and ethical responsibilities associated with AI development and deployment, both to provide secure infrastructure and to serve as intermediaries for AI regulation. Compute providers can play an essential role in a regulatory ecosystem via four key capacities: as securers, safeguarding AI systems and critical infrastructure; as record keepers, enhancing visibility for policymakers; as verifiers of customer activities, ensuring oversight; and as enforcers, taking actions against rule violations. We analyze the technical feasibility of performing these functions in a targeted and privacy-conscious manner and present a range of technical instruments. In particular, we describe how non-confidential information, to which compute providers largely already have access, can provide two key governance-relevant properties of a computational workload: its type—e.g., large-scale training or inference—and the amount of compute it has consumed. Using AI Executive Order 14110 as a case study, we outline how the US is beginning to implement recordkeeping requirements for compute providers. We also explore how verification and enforcement roles could be added to establish a comprehensive AI compute oversight scheme. We argue that internationalization will be key to effective implementation, and highlight the critical challenge of balancing confidentiality and privacy with risk mitigation as the role of compute providers in AI regulation expands.

Executive Summary

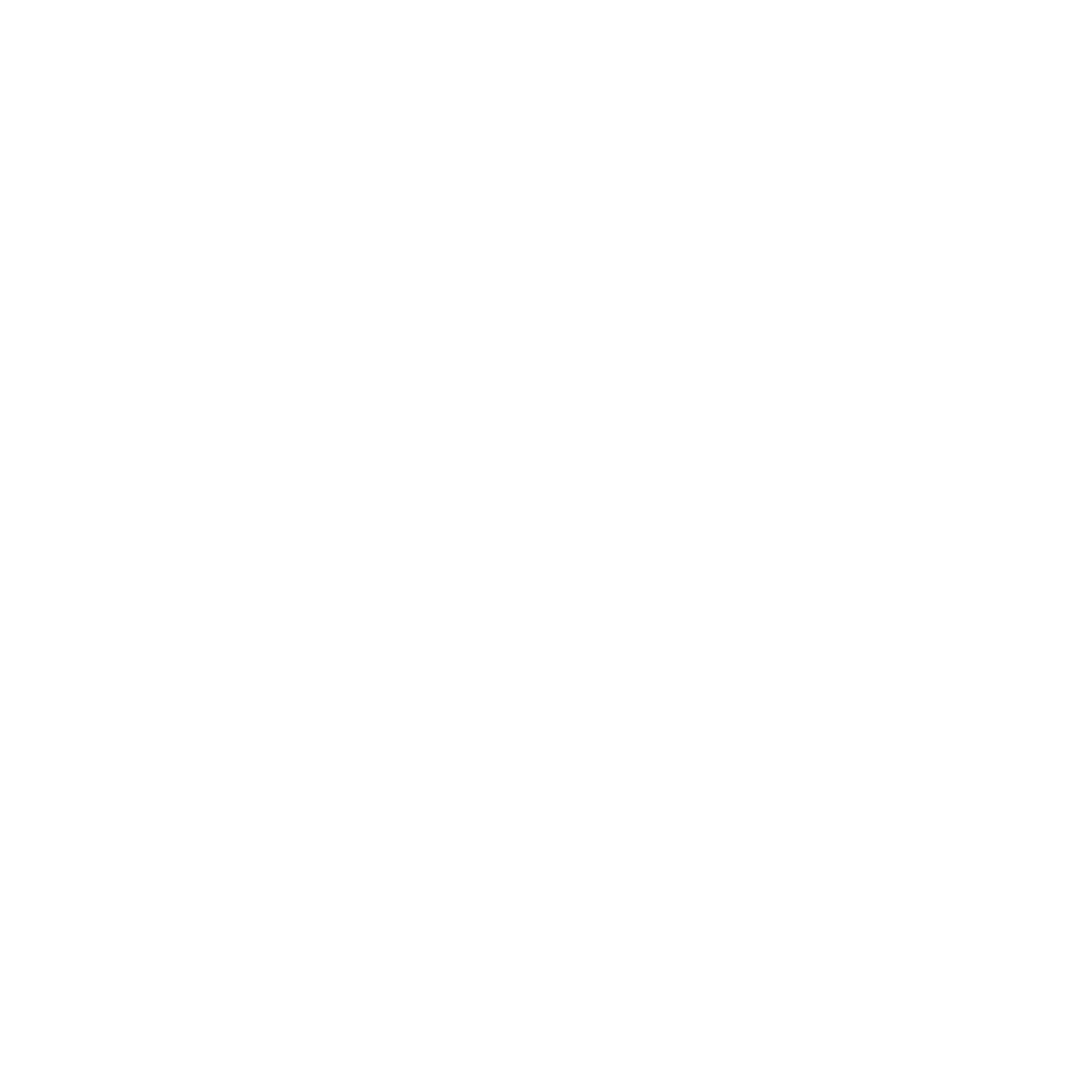

Introduction — Jurisdictions around the world are taking their first steps toward regulating AI, such as the EU AI Act and the US Executive Order 14110. While these regulatory efforts mark significant progress, they lack robust mechanisms to verify compliance and respond to violations. We propose compute service providers, short compute providers, as an important node for AI safety, both in providing secure infrastructure and acting in an intermediary role for AI regulation, leveraging their unique relationships with AI developers and deployers. Our proposal is not intended to replace existing regulations on AI developers but rather to complement them. (Section 1)

Compute Providers’ Intermediary Role — Increasingly large amounts of computing power are necessary for both the development and deployment of the most sophisticated AI systems. Consequently, advanced AI models today are trained, and deployed in data centers, housing tens of thousands of “AI accelerators” (specialized computers for AI applications). Because of the large upfront cost of building this infrastructure and economies of scale, AI developers often access large-scale compute through models like Infrastructure as a Service (IaaS), also often described as cloud computing. (Section 1.1)

Some leading AI firms currently manage their own data centers or maintain exclusive partnerships with leading entities in this domain, known as hyperscalers. Notably, the most advanced AI research is currently being conducted at or with these hyperscalers (e.g., Microsoft Azure, Amazon Web Services (AWS), Apple, Bytedance, Meta, Oracle, Tencent, and Google Cloud). While this situation presents complex challenges for regulatory oversight, our discussion also encompasses scenarios in which compute providers are internal to or closely linked with an AI firm.

We focus on frontier AI systems, which have the potential to give rise to dangerous capabilities and pose serious risks. As these systems necessitate extensive amounts of compute to train and deploy at large scales, targeting compute providers becomes a promising method to oversee the development and deployment of such systems. Furthermore, this target narrows the regulatory scope to the smaller set of key customers who are building AI systems at the frontier, thereby minimizing the burdens associated with regulatory compliance and enforcement. (Section 1.2)

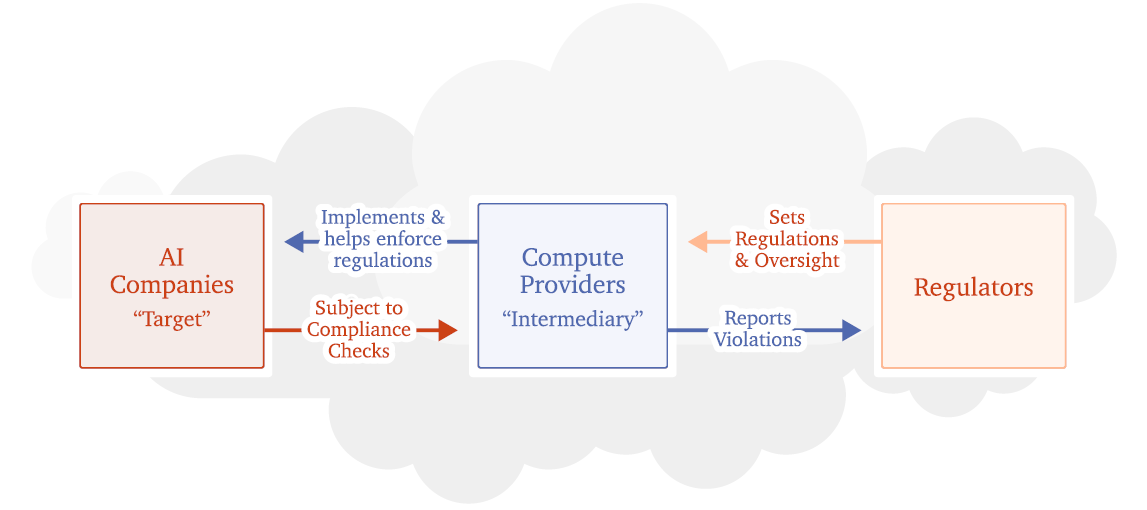

Governance Capacities — We propose that compute providers can leverage their crucial role in the AI supply chain to secure infrastructure and serve as the intermediate node in support of regulatory objectives while maintaining customers’ privacy and rights. They can facilitate effective AI regulation via four key capacities: as securers, record keepers, verifiers, and, in some cases, even enforcers. Reporting represents a related yet distinct dimension, wherein compute providers provide information to authorities as mandated by law or regulations. (Section 2)

Technical Feasibility — Our analysis indicates these governance capabilities are likely to be technically feasible and possible to implement in a confidentiality- and privacy-preserving way using techniques available to compute providers today. Compute providers often collect a wide range of data on their customers and workloads, for the purposes of billing, marketing, service analysis, optimization, and fulfilling legal obligations. Much of this data could also be used to support identity verification, as well as verifying technical properties of workloads. At a minimum, providers have access to billing information and can access basic technical data on how their hardware is used. This likely makes it possible for compute providers to develop techniques to detect and classify certain relevant workloads (e.g., whether a workload involves training a frontier model) and to quantify the amount of compute consumed by a workload. Verification of more detailed properties of a workload, such as the type of training data used, or whether a particular model evaluation was run, could be useful for governance purposes but is not currently possible without direct access to customer code and data. With further research and development efforts, compute providers may be able to offer “confidential computing” services to allow customers to prove these more detailed properties without otherwise revealing sensitive data. (Section 3)

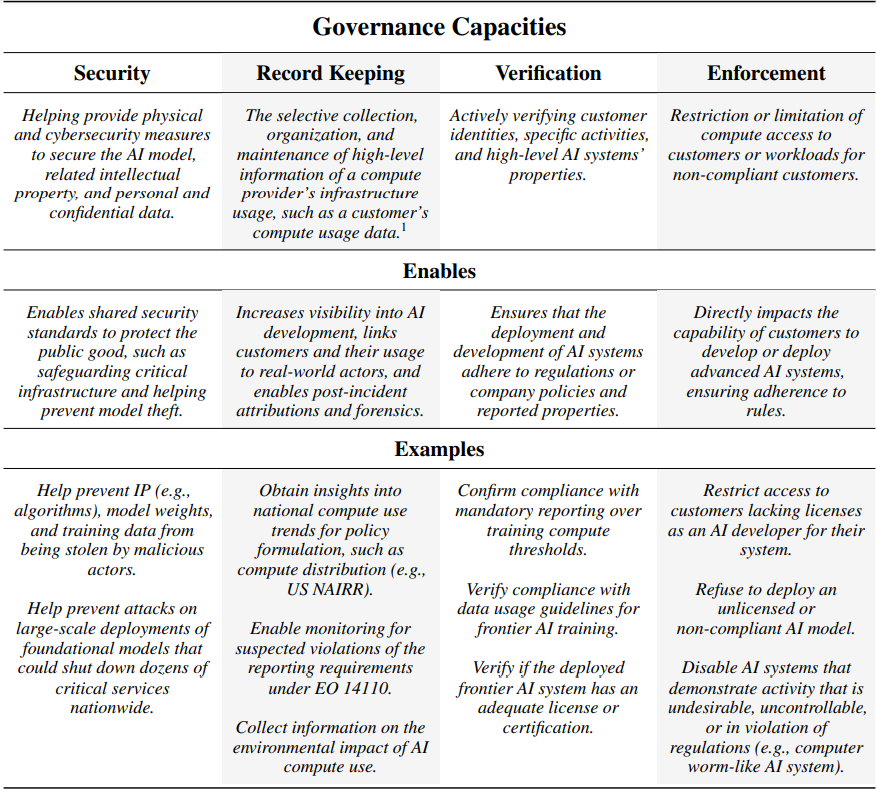

Constructing an Oversight Scheme — Via EO 14110 the US government is already beginning to implement recordkeeping roles for compute providers by requiring them to implement a Customer Identification Program (essentially a Know-Your-Customer (KYC) program) for foreign customers, and to report foreign customer training of highly capable models to government. Expanding the role of compute providers to also record and validate domestic customers using compute at frontier AI thresholds could enable the US government to identify and address AI safety risks arising domestically. Complementing these measures with verification and enforcement roles for compute providers could further enable the construction of a comprehensive compute oversight scheme, and ensure that AI firms and developers are complying with AI regulations. (Section 4)

Technical and Governance Challenges — To realize a robust governance model, several technical and governance challenges remain. These include identifying additional measurable properties of AI development that correspond to potential threats, making workload classification methods robust to potential evasion, and formulating privacy-preserving verification protocols. (Section 5.1)

The success of our proposed oversight scheme hinges on its multilateral adoption to prevent the migration of AI activities to jurisdictions with less stringent oversight. For an international framework to be durable and effective, it must address concerns from non-US governments. Cooperation will need to account for complex privacy and oversight issues associated with globally spread data centers. Compute provider oversight may affect competition in the AI ecosystem and raise concerns about issues of national competitiveness, and, consequently, this may influence the ability of US providers to offer products globally, including to foreign public-sector customers. Industry-led privacy-preserving standards could help ensure trust, but further research is needed to incentivize broad international buy-in to a global framework. (Section 1.4 and Section 5.2)

Conclusion — Compute providers are well-placed to support existing and future AI governance frameworks in a privacy-preserving manner. Many of the interventions we propose are feasible with the current capabilities of compute providers. However, realizing the full potential necessitates addressing technical and governance challenges, requiring concerted efforts in research and international cooperation. As governments and regulatory bodies move to address AI risks, compute providers stand as the intermediate node in ensuring the effective implementation of regulation. (Section 6)

You can read the whole paper here.